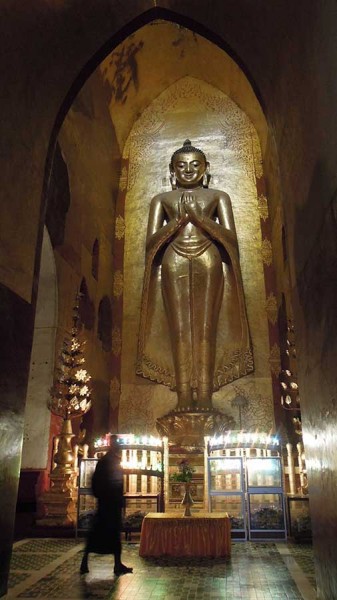

In the era of Trump it’s got harder to tell reality from illusion, but here’s a ceiling from about 300 hundred years ago that shows a real magician in the illusion line at work. The inside of the dome – everything inside the gold circle – looks as if it extends upwards, but it is just painting on a flat canvas. It’s an example of so-called trompe l’oeil, French for deceive the eye. I don’t know why we use a French term – it was never a French speciality.

Some time back I posted about the brilliant trompe-l’oeil by Andrea Pozzo on the ceiling of a church in Vienna, painted a little over three hundred years ago. The photos here show a ceiling in the UK painted thirty years later, by an artist following where Pozzo led the way. It’s in the main entrance hall of a mansion called Moor Park, in the West London suburb of Ruislip, painted in the 1730s. The mansion is now a posh golf club, so it’s not usually open to non-members, but it’s visitable by arrangement, http://www.moorparkgc.co.uk/

The painting of the hallway was done by a trio of Italian specialists in architectural decoration – Giacomo Amiconi, Gaetano Brunetti and Francesco Sleter. I’m not sure whether Brunetti or Sleter painted the illusory dome. They’re not well known. Painting this kind of thing was quite lucrative, but didn’t make you a star in the art world of the time.

Like the dome painted by Pozzo, the illusion in Moor Park is amazingly successful – but only from one viewpoint. As you can see in the lower photo, from everywhere else the dome looks wonky.

Photos © Michaela Butter

Photos © Michaela Butter